AUTOMOTIVE AUDIO SPECIALIST HOWARD BECKER PROVIDES MORE THAN JUST SOUND ADVICE. HE BUILDS ROLLING PLEASURE PALACES FOR HOLLYWOOD’S ELITE.

By Jack Smith

Reprinted from The Robb Report, November 1998

Howard Becker was in his office when Michael Jackson called from Buckingham Palace. “Michael was doing the Dangerous tour through England, and he’d been invited to the palace to meet Queen Elizabeth,’ recalls the wiry, ponytailed Becker. “Michael loves cars, so while he was there, he asked the queen if he could see her car. She said yes and took him down to the garage to see it. It was a customized Rolls Royce, very ornate, with lots of luxury touches.

“Michael liked the car so much he called from the palace’s garage and asked me, “Howard, ca we do something like this?’ I remember sitting there, wondering just what it was he was looking at. I mean, this was the queen of England’s car.”

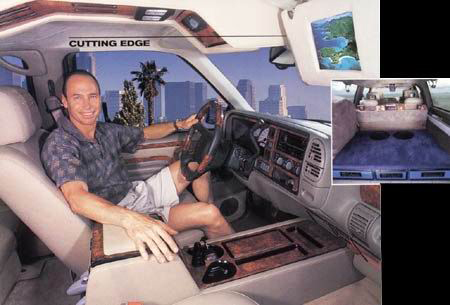

Jack-o’s request may have been bewildering, but Becker never doubted that his company, Becker Automotive Design, could create a vehicle equally opulent. In Becker’s hands, even the most prosaic vehicle can be transformed into a high-performance, status-laden Xanadu, a rolling pleasure palace replete with sound and entertainment systems to dazzle the eye and thrill the senses. Laser detectors and closed- circuit systems alert to trouble ahead and behind; satellite navigation equipment pinpoints course and location; and suede-covered, individually customized seats with built-in massage units make even a trip to the cornet store a sensuous experience.

To be sure, the Becker treatment doesn’t come cheap. A sport utility that originally cost $30,000 may roll out of his shop sporting another $100,000 worth of amenities. To Hollywood’s elite, however, the results are well worth the expense. Over the past dozen years Becker has developed a celebrity clientele to rival that of the William Morris agency, while his shop, an ersatz chateau that formerly housed an Italian restaurant, draws as many celebrities as Spago.

Where Los Angelinos once dined on mussels marinara and osso buco, there are now control panels and speakers, custom-made seats, mats, and alloy wheels on display. Becker’s desk site unceremoniously in the center of the former dining room, and the walls are hung with autographed pictures, posters, and album covers from his admirers, from the king of pop to Motown mogul Berry Gourdy to stars Barbara Streisand, Whoopi Goldberg, Jerry Seinfeld, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Reiser, Steven Spielberg, Dionne Warwick, artist David Hockney, Cheech Marin, Snoop Doddy Dogg, M.C. hammer, Dr. Dre, and Mel Torme.

At the only other desk in the office is Larry Steon, who manages the company’s conversion sales, “We have a regular checklist for perspective customers to use in selecting their upgrades. Most of them have no idea what they’re getting into.” He holds up one such form. “This fellow here has checked off special wheels, tires, suspension, brakes, paint, projector lights and fog lights, security system, multiple TV’s, a sound system, GPS tracking. . . That’s at least $100,000 worth of extras.”

But the change is dramatic. Outside, a fully converted sport utility rolls past, its original identity erased beneath the dark monochromatic sheet metal and cladding. The smoked glass shields the driver from sight, and as the car rolls past it howls its metamorphosis to the world, the subwoofers thumping like fists against the office windows.

However lavish the amenities, Becker emphasizes that the majority of his buyers consider the services a necessity rather than a luxury. “Take Slash from Guns N’ Roses or rappers like Dr. G and Snoop Doggy Dogg,” Becker suggests. “No matter what you think of them or their music, they’re serious musicians. And when they’re driving along in their cars, it’s their own music they’re listening to; they need to hear everything. They’re very focused once they get into their own element.

“The big issue is the overall sound quality; if it’s good enough, everybody likes it,” he adds. “Musicians are very demanding customers.”

They can be appreciative as well. After Berry Gourdy spent over an hour auditioning the sound system Becker’s technicians installed in his Rolls-Royce, he assigned the same crew to redo the media room at his home.

Earlier that morning Becker had driven an hour north of L.A. to a set where repeat customer Will Smith was shooting a new version of The Wild, Wild West, the Robert Conrad sci-fi/Western of the 1960’s. Becker’s shop was doing a jaw-dropping transformation of Smith’s Suburban including textured Bentley black carpets, the best black leather with leather suede, and custom Japanese ash wood treatments with silver highlights.

The CD sound system in Smith’s rig represents the culmination of everything Becker and his highly trained corps of technicians have ever learned. The equipment begins with and $8,000 Sony XES dash- mounted head unit which connects via a non-distortive Kimber home stereo cable to the speakers. “You wouldn’t believe the difference a cable can make,” says Becker. “It sweetens the music.”

The speaker system includes 16 Dynaudio speakers from Denmark discreetly mounted in the front door, pillar posts, rear door, and third door with two large AVI subwoofers mounted under a false floor in the cargo area. The amplification is by McIntosh Audio Labs with a parametric equalizer affording 10 channels of fine tuning. Other sound sources include tape cassette and radio, a DVD player, VHS, and two Sony Play Stations, with three 6.4-inch high-resolution liquid crystal display screens, one mounted on the front passenger visor and two behind the front seat headrests. “It becomes a true mobile home theater, rather than an audio or video system in the narrow sense,” says Becker. “When it’s all put together, people just loose control.

Whether a movie star or a rapper or a CEO of an international conglomeration, says Becker, all of his customers have one thing in common: “Nobody wants to just listen to the music in their car; they want to luxuriate in it.”

This insight launched Becker into the forefront of the L.A. auto-sound scene in the late 1970’s. “Somebody would come into the shop where I worked for an extra speaker in their car. I would ask them, ‘Do you really want an extra speaker, or do you want more music? Do you want a more exciting ride? When you pick up your date on Friday night, do you want the passenger compartment to be filled with sound and rhythm?’ I wasn’t selling electronics. I was selling an experience.”

Becker’s toughest sell, though, was his own father, Bernard, who originally owned the shop. “It was really more of a repair shop than anything, and my father didn’t want me in the business. He had bigger dreams for me. He wanted me to go to law school and become a lawyer.”

The way Bernard Becker saw it, young Howard was bound to succeed as a lawyer. After all, his son had everything else, both on the athletic field and in the classroom. In 1966, Becker won a track scholarship to the University of Southern California, where he competed in both 400- and 800-meter events, ultimately earning world ranking in the quarter mile in 1969. “Those were great days,” he reminisces. “In ’68 and ’69 I spent the summers traveling across Europe with Bob Seagren, who was America’s premier pole-vaulter, and competing with the U.S. track team.”

They were also crazy days. “It was the ’60s. The whole world was expanding and breaking with the conservative parameters of the past. We were looking at our universe through a new prism. All sorts of experimentation was going on.” He smiles. “Fortunately, track kept me straight. So in 1970 I got my B.A. in psychology and entered business school.”

Once in the work-a-day world, he discovered there was much he hadn’t learned in business school. “I got me M.B.A. in 1971 and went to work for a management consulting firm. I worked with $1 [million] to $5 million firms doing financial planning, marketing, and capital restructuring. But I found I was becoming envious of the business owners. I was drawn to the nitty-gritty of running my own company.”

Becker was becoming an entrepreneur, but he knew nothing about the world of the entrepreneur. “At that time, American universities didn’t take entreprenuership seriously,” he explains. “Now, it’s big, but back then it was mom-and-pop stuff. Business schools were geared to prepare their graduates for careers in marketing of finance with Fortune 500 companies or on Wall Street.”

Becker decided to do something about that. First he immersed himself in the literature of entreprenuership. Then, at the age of 23, he started teaching it. “It began as a noncredit course at Pierce Junior College in Woodland Hills, Calif. I remember the very first class. Over a hundred people showed up, most of them business owners. I’ll never forget the feeling of walking down the aisle to the front of the auditorium. My voice squeaked as I started to say, ‘Hi, I’m here to teach you how to run a business.'”

Shortly thereafter Becker’s course became part of the accredited curriculum at California Lutheran University, where he continued to teach for the next 20 years. The teaching experience was gratifying, but five years into the stint the former track star began reassessing his life and goals, his likes and dislikes. His training in psychology enabled him to communicate effectively with people and understand their wants and needs. Further, he’d always been an affinity for both music and cars. Not that he had any musical talent, but it was music-Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix- that had defined his generation. At the same time, there was his penchant for high performance, whether on the athletic field or on the highway. He had been teaching entreprenuership for five years; now perhaps it was time to practice it. And what a better place to do it that in his father’s car radio shop.

The Biggest Critic

Bernard Becker was less than enthusiastic about working with his son. “When I first went to work for him, he would introduce me to his customers by saying: ‘This is my son the schmuck; he went to college to work at my radio shop.'”

The younger Becker was initially frustrated. “I really wasn’t very good with a screwdriver. I was all thumbs at installing electronic gear. Dad would give me jobs like stacking the shelves, just to keep me out of his way.”

But as Becker soon proved, he had a knack for selling. “I didn’t just want to repair car stereos, I wanted to improve [their sound]. Dad had always prided himself on doing a job as economically as possible. The typical car of that time had an AM/FM radio in the dash hooked up to one monaural speaker. When customers wanted to convert to an 8-track tape and stereo system, Dad would say ‘Keep the speaker in front; I’ll just add another in the back. It’ll be cheaper and save you money.’ But the way I saw it, it wasn’t gizmos people wanted-not more radios or speakers or more amps, but more music-a deeper, richer sensation.”

Soon, woofers were booming throughout the surrounding neighborhood and so was word about the Becker’s radio shop. “The shop was situated in Hawthorne, a predominantly black neighborhood north of LAX, so our clientele wasn’t affluent, but after a motor and four wheels, the people who came into the shop had to have music.”

The first breakthrough came in 1997, the result of attitude as much as an advancement in technology. “e looked at the car as if it were a home. What this means is, we took combinations of speakers- bass, midrange, and tweeters-and built them into the car much as you would build an in-home stereo system. It was the first time anybody had done that,” says Becker.

Meanwhile, across the street from Becker’s shop, the competition was cutting prices. “It was a place called Leo’s, and they sold stereo equipment at a discount. Some customers came to us first to see what they wanted, then went across the street to Leo’s to buy it cheaper.

“But in a way, the presence of Leo’s helped to differentiate us from conventional automotive stereo shops. They were selling a commodity, and when you’re doing that, all you want to do is move products.

“We were selling value-added, and so we focused on quality. We were always learning and looking for ways to improve sound. A car isn’t like any other environment; it presents special challenges. The smaller the car, the more difficult it is to work with; the larger the car, the more room you have to mount equipment. Window glass can be particularly problematic. It reflects sound, while carpets absorb it. Audio direction is another consideration. Speakers are usually mounted in positions ‘off axis’ to the passengers’ ears, and of course the driver never sits in the middle of the car.”

A second and bigger breakthrough can in 1979, when Becker committed what some claimed was automotive heresy. Becker purchased a new Mercedes 450SL, ripped out its factory-installed sound system, and replaced it with his own design incorporating home stereo components and speakers. Then he drove it down Wilshire Boulevard to every Mercedes Benz, Rolls-Royce, Porsche, and Ferrari agency in Beverly Hills. “Some of the people at the Mercedes-Benz [dealerships] said, ‘How dare you put anything but factory equipment in that car?’ That was maybe 25 percent of them. The rest of them were amazed when they heard the difference.

“Then I outfitted some of the sales managers’ cars with similar equipment. It was a big investment, but the celebrities weren’t coming to Hawthorne, so we had to come to them. It gave the salesman something extra to sell. The Ferrari or Porsche of Rolls-Royce salesmen would ask a customer, ‘Say, would you be interested in upgrading your sound system?’ Considering that we were in the music capital of the world, there were lots of reasons for them to say yes.”

The first celebrity to nod an affirmative was Rod Stewart. “He had a Porsche Turbo, and we installed about eight or 10 speakers in his car. Then Barry Manilow brought us his convertible Rolls-Royce; it already had been redone, and it was a disaster.”

In 1984, Becker moved the company, by then known as Becker Automotive Design (B.A.D.), to its present site, a half-block south of Beverly Hills, and began routinely installing upgraded sound systems for every Porsche, Mercedes, BMW, Rolls-Royce, and Ferrari dealership from San Fernando Valley to Long Beach.

Utilitarian Luxuries

The shape of today’s celebrity transportation arrived at Becker’s shop in the early 1990’s. However, it wasn’t in the form of the low and slinky and outrageously expensive; it was big and boxy and made for the mass market.

For Becker and the four-wheel-drive sport utility, it was love at first sight. Here was a vehicle that begged for added value – not just in the way it sounded, but in the way it looked and handled – and Becker Automotive Design was just the company to provide it. “Snoop Doggy Dogg and Warren G. owned two of the first SUVs we totally customized,” says Becker, “and rappers have a tremendous influence in the L.A. culture, not just on fashion and music, but also in the cars that entertainment and sports stars drive. Now, in the music and sports world, people simply have the have an SUV.”

The appeal of the SUV, explains Becker, begins with its versatility and size. “But they can be improved upon from several points: power, brakes, suspension, exterior and interior aesthetics, and electronics. Once you do that, you have an SUV that feels like a European high-performance luxury car, only the SUV has more value and utility that the luxury car. You can pull up next to an exotic or luxury vehicle, and all the excitement is in the truck. They’re tough, they build value, and they give their drivers great pride of ownership.”

The possibilities are evident in the gleaming metallic khaki GMC Yukon that stands outside the door to Becker’s office. “This one’s headed for Kuwait,” says Larry Seton, who handles sales of SUV conversions for B.A.D. “It’s supercharged to produce and extra 100 horsepower. It’s got special brakes, upgraded suspension, and, naturally, TV and video games built into the backs of headrests. The massage units are built into the seat backs.”

A dark blue Rolls Royce stands next to the Yukon, and Seton opens the trunk to display the heavy woolen mat embroidered with England’s Order of the Garter. No less conspicuously, the D-pillar sports a metallic heraldic medallion. “Must be the royal family’s coat of arms,” says Seton, with a shrug. Inside, the rear passenger compartment is decorated with antique lamps and a glass vase.

“Oh, the Rolls?” Becker responds brightly, as we reenter the office. “We did that for Michael Jackson after he saw the queen of England’s. He says he likes his better than hers.”

Becker Automotive Design has been awarded Robb Report’s prestigious Best of the Best for 20 years.

Becker Automotive Design has been awarded Robb Report’s prestigious Best of the Best for 20 years.